Articles

Understanding Breakevens, Part One: Laying the Groundwork for a Misunderstood Idea

By Osama on November 4, 2025 in Latest News

Global oil markets are in one of those periods where it seems that it is finding a balance. Demand remains questionable, with the IEA’s Oct 2025 Oil Market Report projecting global consumption just above 750,000 million barrels per day and supply capacity likely to exceed that by roughly 1.5 million barrels per day as new projects in the U.S., Brazil, and Guyana ramp up. Shale output so far remains strong with new highs touching in August 2025. This is in line with Primary Vision’s Frac Job Count and Frac Spread Count projections as both have registered gains since July 2025 hitherto. But there are some reports that says decline rates are steepening, and investors want cash flow rather than volume. The question that follows is simple: what oil price does shale really need to keep going?

This brings us to one of the most widely misunderstood term: Breakeven. It is one of those words that gets thrown around constantly in oil and gas, but it rarely means the same thing twice. You’ll see an investor slide claiming “our Permian wells break even at $15 a barrel,” a Dallas Fed survey saying U.S. “shale needs $65", and a “government budget warning that fiscal breakeven is closer to $80". All of those numbers are real in their own way, but none of them are talking about the same thing. That’s why we think it’s worth slowing down and asking a basic question before we go any further: what does breakeven actually mean, and how should we use it?

In oil and gas there isn’t just one breakeven. Yes! That is right.

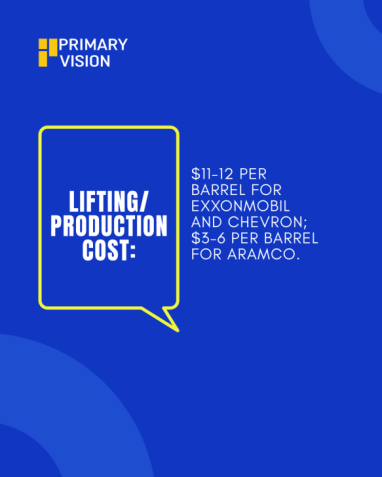

At the lowest level, there’s the lifting or production cost ie the expense of keeping existing wells flowing. For the big U.S. majors, that’s around $11–12 per barrel (based on Q2 2025 filings from Exxon Mobil and Chevron), and in the Middle East, for instance for Aramco, it can be as low as $3–6 per barrel.

Above that sits the half-cycle breakeven, These include drilling and completion, operating costs, royalties, and transport. They show what it takes to bring a new well online. According to the Dallas Fed Energy Survey (2025), U.S. oil producers require an average of around $41 per barrel to cover operating expenses for existing wells. By contrast, EIA data for 2024 indicate that break-even prices for new production in the Permian’s Midland and Delaware basins stand higher, at approximately $62–64 per barrel.

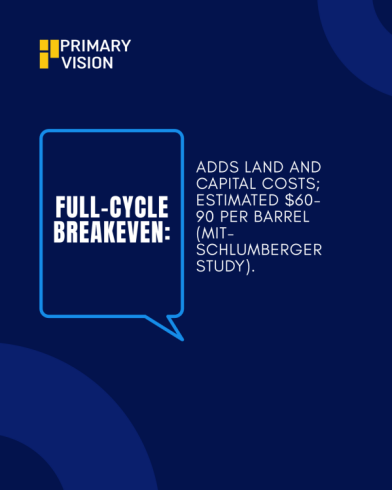

Then comes the full-cycle breakeven that includes land costs, corporate overhead, and capital charges. This is the more realistic measure of what it takes for a new project to pay for itself; The ranges vary but one MIT-Schlumberger study (Kleinberg et al., 2017) put in the $60–90 range.

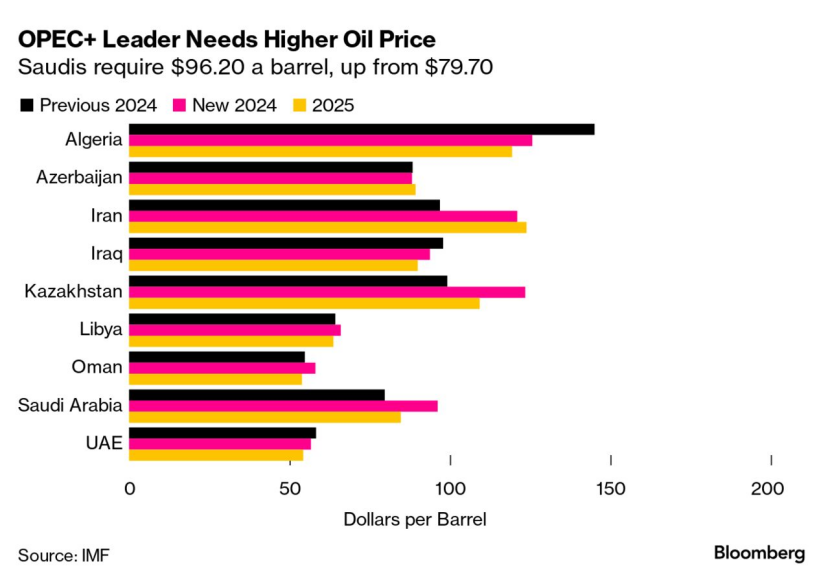

And finally there’s the corporate or fiscal breakeven: For oil companies this includes dividends, debt service, and capital spending across all assets. For countries, it means the oil price needed to balance national budget. For shale companies, that tends to sit in the mid-$60s, while for oil-exporting states the fiscal versions are higher. In the IMF’s latest Regional Economic Outlook statistical appendix, the projected 2025 fiscal breakeven oil prices are Saudi Arabia $83/bbl, Kuwait $81.8/bbl, and Iraq $92.4/bbl.

The danger is that these layers get mixed together in public debate. A chart showing production costs at eleven dollars doesn’t mean a company can profitably expand at eleven dollars. An investor slide with a fifteen-dollar Permian breakeven may leave out land and corporate spending. And when analysts compare corporate and basin numbers without noting definitions, they turn data into noise.

That’s why we’re starting here. Before we publish spreadsheets or claim which basin has the lowest breakeven, we want to make the concept itself clear. The above discussion sheds light that why no single figure can represent the cost reality of shale or any other producer. In the next installment, we’ll look at what companies themselves disclose as their breakevens and whether those numbers really describe economic resilience or just investor optics.

Tags: